When he woke up, it was quiet around him. A light mist drifted over the desolate landscape, and he rolled onto his stomach. His foot was caught in the barbed wire. He hadn’t made it to the trench, and something hard had struck him in the back. He was cold, terribly cold, and he pulled the dirty and torn coat tighter around his shoulders. He thought of the landscape as it was two years ago—blooming fields and trees, a sky that always promised a good morning. And today? A no-man’s land of mud and trenches, contested from all sides, drenched in the blood of those who were revered as heroes far from this hell.

When he woke up, it was quiet around him. A light mist drifted over the desolate landscape, and he rolled onto his stomach. His foot was caught in the barbed wire. He hadn’t made it to the trench, and something hard had struck him in the back. He was cold, terribly cold, and he pulled the dirty and torn coat tighter around his shoulders. He thought of the landscape as it was two years ago—blooming fields and trees, a sky that always promised a good morning. And today? A no-man’s land of mud and trenches, contested from all sides, drenched in the blood of those who were revered as heroes far from this hell.

It was perverse and inhuman—a slaughter on a gigantic conveyor belt of death, to which new faces and fates were fed every day, ground down into blood, mud, and dirt. It was said to be an honor to die for the fatherland, but here, no honor was to be found—only an endless nightmare.

His back ached terribly, and he struggled to breathe. There he lay, hidden in the mist and mud, and the only sound he could hear was the soft murmur of the wind brushing over the craters and holes in the ground, whistling through the wooden reinforcements for the ever-present barbed wire. He was freezing miserably and closed his eyes for a moment. A brief pause in this madness of false honor…

“Have you been good?” It was the voice of Santa Claus, oddly sounding like his uncle’s, that he heard. He was six years old, standing in his best clothes before the candlelit Christmas tree, hands neatly folded, gaze fearfully lowered yet full of anticipation. They had bought him one of those new dolls—a bear with a button in its ear. Just the one he had always wished for. He saw his parents’ eyes, both satisfied to see his joy. Julius, yes, that’s what he would name his bear…

The wind was icy, and the cold spread from a spot on his back further and further into the rest of his body. He shook off the memory and stood up. He would have to keep moving if he wanted to survive. But where? He had lost his bearings and no longer knew where the constantly shifting front line was. Was he in enemy territory? Or was he still on German soil? He didn’t know, and even if this damned mist hadn’t been there, every corner of this playground of death looked the same. Digging his fingers into the ground, fear and despair brought a tear to his eye—one of many that had already soaked this soil and turned it muddy.

He was weak, and the wind whistled over him—reminding him of his mother, how she placed her hand on his shoulder when saying goodbye, looking at him with a mixture of pride and fear. He thought of how his father had told him not to be afraid, that the enemies posed no danger, and that he would be doing a good Christian deed by putting an end to those dogs. The image of the enemy had changed here. At some point, the monsters turned into humans, and later, the humans became shadows, empty eyes staring back at him without hope for a tomorrow—reflecting what he himself had become: an emaciated body with glassy eyes, long having lost faith in why he was here.

His father—the man who had taken Julius from him on his twelfth birthday. Boys don’t play with dolls, he had said. Instead, he was given an army of tin soldiers. Cold and smooth in their painted uniforms. Each one identical to the next; the military had no room for individuality. Row upon row, armed and smiling, they marched into a war that would never end for them. But none of them could offer the same comfort in his dreams as his beloved bear, Julius. He hadn’t dared to cry back then, hadn’t dared to plead with his father to give him back his Julius. He knew his father wanted to make a man out of him, not a whining boy…

Once again, he closed his eyes, his thoughts straying from Julius back to his mother, back to the safe confines of a childhood that now felt so terribly distant. The wind swept over him, carrying with it a burst of warmth—perhaps from a fire burning somewhere nearby. He tried to pull himself forward, struggling against the cold and his weakness, when his fingers touched something strange. A familiar shape, damp fur—not the hair of a comrade or a horse; it was too soft for that. He curled his fingers around the object and pulled it from the mud. It was a teddy bear, staring at him with one eye while the other dangled from a piece of thread.

He began to laugh—with the fire behind him, sending a warming current in his direction, and before him, a battered old stuffed bear appearing just as he was thinking of his own bear. He had loved his Julius, the little soft companion. A silent comrade who accompanied him in his dreams and kept the monsters in the darkness of his childhood room at bay. A silent, furry, loyal watchman with a button in his ear.

He clutched the teddy bear and crawled a little further forward. The warmth was now closer, and the wind carried its scent to him. It smelled of honey cake and warm milk—perhaps a new poison gas? He had heard from others that some chemical weapons gave off a sweet, almost pleasant scent. No, he didn’t want to die—not like this, not in the anonymity of the field. He didn’t want others marching over his corpse, his body crushed under the thunder of mortars, becoming part of the mud to which everything here eventually turned.

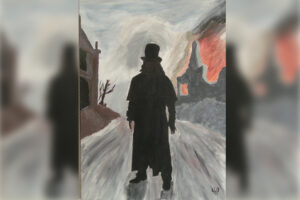

Gathering his strength, he stood up—leaving his rifle behind. The time for fighting was over for him. He didn’t look back; he just wanted to leave. Holding the teddy bear, he took one painful step after another. It took time for his body to realize there was still energy left in him. He began to walk lightly, step by step, away from here, as far away as possible from Belgium’s shattered and desecrated soil.

The wind at his back grew stronger, aiding his escape across the field. But he had to keep running, for the sweet scent followed him on the wind. He leaped over trenches, stumbled over wire, and ignored the stabbing pain hammering in his back more and more with each step forward. Gripping the teddy bear in his hand, the wounded soldier fled through the murky mist—toward wherever „forward“ might lead.

Someday, he stumbled, fell back into the mud, and touched something hard. His fingers closed around a picture—his picture. It must mean that his father or one of his brothers had followed him to war. It didn’t matter how unlikely it was to find traces of his own past in the chaos of mud, blood, tears, and shattered bodies. He stood up again and called out for him, shouting as loudly as he could, more tears soaking the softened ground…

And there was that sweet, enticing scent of chemical death again—he kept running, calling his father’s name without receiving an answer. While running, he placed the picture in his breast pocket, something he wanted to take home. Eventually, he stopped calling, just running forward until the mist began to lift and he reached the edge of a small forest. There were still trees here, scattered shrubs. Life that had not yet been extinguished by the war and the constant roar of mortars and gunfire. He must have run far, very far, and still, he didn’t know where he was.

He stumbled through the forest, the sweet smell still behind him, and eventually reached a clearing. He wasn’t alone anymore. Some of his comrades had likely fled in the same direction to escape the toxic cloud. They didn’t look much better than he did, but they had found a new leader—his father. In a comparatively clean uniform, he stood before them and explained where they would go next. A new order from above was to bring them home, and he had been tasked with leading them there. His father saw him and beckoned him over—no reprimand for holding a teddy bear instead of his rifle, no word of reproach, just a tear rolling down his old father’s face as he looked at his son…

The wind whispered softly over Belgium’s soil, brushing over the lifeless body lying in the mud. A gunshot wound had pierced through his back into his lung, ending a young life and robbing it of its future. The soldier’s right hand was stretched forward, as if reaching for something very dear to him, something hidden from other eyes. His name is recorded nowhere—an unknown, sacrificed for the madness of a few. Another story of a person whose tale the night wind tells, that wind which knows the names and stories of countless others and which will one day whisper our names too…